Ghost Bike Vigil for Steve Studt

On Friday, there was an article in The Coloradoan about the sentencing of Jose Piñon in the death of local cyclist Steve Studt. Last month, Piñon pled guilty to felony negligent homicide only days before his trial was scheduled to begin. He was sentenced to a short jail stint, a hefty community service requirement, and as a result of his immigrant status and felony plea, he may face an uncertain future in the US when he reapplies for residency.

The comments on various news articles about the sentence predictably covered the spectrum from blaming Mr. Studt, to gross insinuations relating to the fact that English is not Mr. Piñon’s first language, to criticizing a sentence that felt to some observers like a slap on the wrist.

The first thing that came to my mind when I heard about Piñon’s last minute guilty plea was relief that he had decided to accept responsibility for his negligence. Jury trials are very expensive and time-consuming for our legal system and law enforcement.

Second, I braced for the normal victim-blaming. Sure enough, it didn’t take long. To hear some commenters explain it, bikes are a menace that should be banned from many roads.

City and county safety reports, easily available to review, tell a different story. Traffic violence – bodily injury and death resulting from traffic crashes – is among the leading causes of accidental death in the US and in Larimer County. It is also a huge cause of serious injury. But bikes are a very marginal contributor, both in absolute numbers and relative to their mode share, compared to single occupancy vehicles (SOVs).

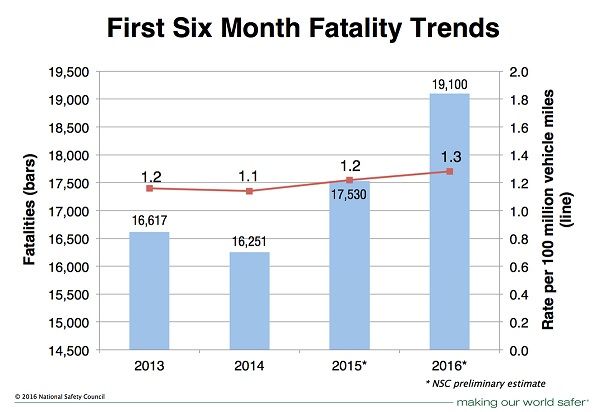

How dangerous are cars? This year, the National Safety Council predicts nearly 40,000 deaths in the US from traffic violence. That’s a 7% increase from 2015. For perspective, 15,000 Americans die in criminal violence each year. 4,000 American soldiers died in a decade in Iraq, and just over 60,000 were killed in Vietnam. Thats right–cars kill as many Americans in less than 2 years as the the Vietnam War killed in 20.

In 2015 in Fort Collins, there were over 900 traffic crashes that resulted in injury. Roughly 4% involved bike riders. Less than half of that 4% were the fault of the bike riders, who in Fort Collins account for ~7.5% of commutes.

If, as a thought experiment, you took every bicycle off the road in the US, car crashes would still kill nearly 40,000 people a year.

Now, flip that: take cars off the road and leave the roads to bikes, pedestrians, and mass transit. I think you would find you’d save in the ballpark of 39,000+ lives per year.

Dispatching the argument that bikes are a safety menace, and the attendant false equivalency of bad actors on bikes being a comparable safety threat to bad actors in cars isn’t challenging. Changing hearts and minds around auto-centrism certainly is.

My third reaction was a wave of emotions around Piñon’s residency status, the possibility that his felony plea will mean he is deported, and disgust with some of the comments about the fact that in court he spoke through an interpreter. As a native English speaker, if you were on trial in a language other than English, you would be nuts not to enlist a professional translator, no matter how competent you were in a second language. Too much is at stake to risk an amateur mistranslation.

Bike Fort Collins will not tolerate exploitation of this tragedy to advance anti-immigrant sentiments. That’s not who we are. We are committed to public safety and public health engagement that is more inclusive, and reaches everyone in our community. In the US, no demographic group has more at stake in really addressing bike safety than Latinos. BFC’s commitment to safe streets means we are committed to serving and working with populations who are most vulnerable and have the most exposure to the threats we’re facing.

As for the sentence itself: Some say 90 days in jail is inadequate. I reckon most of those folks have never spent 90 days in jail as a 70-year-old man. I spent the night once and it made a lasting impression. I was 20.

Studt’s Ghost Bike

For a bike community as large and tight-knit as ours, there is a charged and painful question at the heart of sentencing for crimes against bike riders. Robust prosecution and harsh sentences are seen as signaling a commitment to “justice.” Community service and plea deals are seen as an affront and a lack of concern for bikes and the lives of bike riders. But evidence I am aware of is quite convincing that the draconian incarceration terms we as Americans call for do nothing to support actual improvements in public safety and they do so at a very high cost. Accountability is important. Examples are important. But so is being responsible with our public dollars, and rational in our priorities. (as an aside, those I have asked from Belgium, Denmark and other countries with very high bike-ridership and very low injury and death rates all expressed doubt that under similar circumstances in their countries, Mr. Piñon would be incarcerated at all).

Jail, like the court system, is very expensive for the county and the public. And one has to wonder if the money we use to hold people in county jail could be better applied to things like safer overpasses and a more complete regional bike network. Crime scene investigations, trials, and incarceration are expensive. Public funds are finite and constantly under threat.

Traffic violence sometimes involves criminality, but it ALWAYS involves infrastructure. In the past few years, the deaths of cyclists on roads in Larimer County involved various degrees of criminal liability (including fleeing the scene, which is a separate and indefensible act). But they’ve also consistently involved circumstances in which complete streets or reasonable alternative routes would have likely kept negligence from resulting in the death of vulnerable users. The great tragedy of bike-related traffic fatalities in Larimer County in the last few years is how many of them occurred at places that many of us already knew to be unsafe, yet not enough has been done.

In a pragmatic conversation about responses to traffic violence, there are clear best practices for how effective different strategies are. Least effective are personal protective measures like safety gear, seat belts, and helmets. This is not to say that personal protective gear is useless, but in a serious reckoning with our current traffic safety crisis, they’re a very limited tool for a variety of reasons and should not be a high priority or centerpiece of any traffic safety plan. Most of the time when someone says an airbag or helmet or seatbelt saved their life, it’s also true that it saved their life from something that should never have been allowed to happen in the first place.

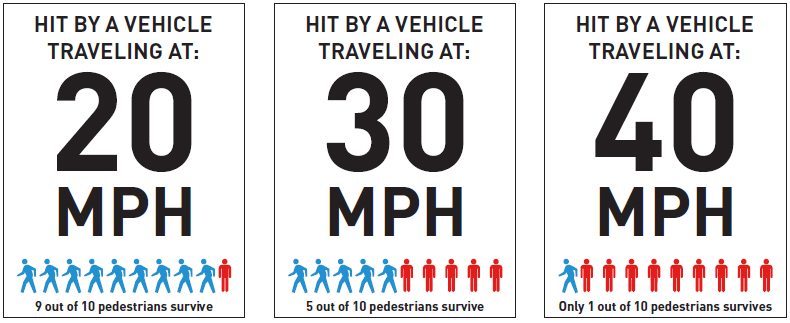

Similarly inefficient are administrative controls; speed limit and traffic code fit here. Yes, speed is a critical factor in traffic violence. Chances of survival of a traffic crash plunge from 90% to 10% when vehicle speed increases from 20 mph to 40 mph. But speed limits, by themselves, are less effective at controlling speed than they are at generating revenue from tickets. Think of a street or road near you that frequently hosts radar speed traps. Chances are good that there’s something wrong with the street that demands re-engineering, not more radar guns.

Similarly inefficient are administrative controls; speed limit and traffic code fit here. Yes, speed is a critical factor in traffic violence. Chances of survival of a traffic crash plunge from 90% to 10% when vehicle speed increases from 20 mph to 40 mph. But speed limits, by themselves, are less effective at controlling speed than they are at generating revenue from tickets. Think of a street or road near you that frequently hosts radar speed traps. Chances are good that there’s something wrong with the street that demands re-engineering, not more radar guns.

See where this is headed?

If our goal is really fewer deaths on our streets and roads, defaulting to criminalizing and harshly punishing people who make bad decisions on badly engineered roads might not always be the most effective or most cost effective response to traffic violence. We should also take seriously the need to build a transportation system in which it’s much harder for bad decision-making to end tragically.

If you are angry that our city and county and state don’t take the safety of vulnerable road users seriously, you are right. If you think that our justice system should be a centerpiece of changing this, rather than our city and regional and transportation plans and budgets, and city council and county commissioner elections and policies, you are settling for an expensive and incomplete downstream response to an upstream problem. You are treating symptoms, not the disease.

We will be more successful in building safer streets when we are less concerned with how long offenders spend in jail and more interested in questions like:

- Why is it so easy to get a driver’s license, and so hard to lose one?

- Reciprocally: Why are we so reluctant to support policy and infrastructure that make living without a car or even driving less more feasible and less debilitating?

- Why are the public safety, health, environmental, and economic impacts of over-reliance on single occupancy motor vehicles broadly subsidized?

- Why do we prioritize increasing capacity for law enforcement under the pretense of public safety, when traffic violence due to auto-centrism and bad infrastructure and land use is a much greater threat to public safety than crime is? Why are we told that we can’t afford public transit and sidewalks when what we really can’t afford is more sprawl, more parking lots, more congestion, and more summers where getting across town by car is an all-day adventure due to construction?

- Why do we resist development that deemphasizes SOV dependency?

Ernesto Weidenbrug’s Ghost Bike

These are, of course, complicated and nuanced challenges than require more sustained work and attention than locking up the symptoms. But complicated challenges demand complicated conversations, and usually, solving them requires collective will for change. It will require acknowledgement that a more just, safer community is a hands-on commitment. And it will require that we not allow the media or the public at large to change the subject when we are reminded by tragedy of the gravity and scope of the work.

Streets and roads are the circulatory system of our neighborhoods and cities. They connect us to work, school, food, church, civic engagement, recreation, and opportunity. And their use is a right that is not reserved for one type of user over all others. The bigger Northern Colorado gets, the more of us there are, the more urgent it becomes that we center our cities and streets around people, rather than cars.

Chris J Johnson

Executive Director

Bike Fort Collins